© Texas Education Agency (TEA).While attempting to start Logger Pro, you may encounter the following issues: We recommend using aĪuthors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs Use the information below to generate a citation. Then you must include on every digital page view the following attribution:

If you are redistributing all or part of this book in a digital format, Then you must include on every physical page the following attribution: If you are redistributing all or part of this book in a print format, Changes were made to the original material, including updates to art, structure, and other content updates. Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses theĪnd you must attribute Texas Education Agency (TEA). Is the answer reasonable? Are the units correct? If the object does accelerate in that direction, Fnet x = m a. If the object does not accelerate in a particular direction (for example, the x -direction) then Fnet x = 0.

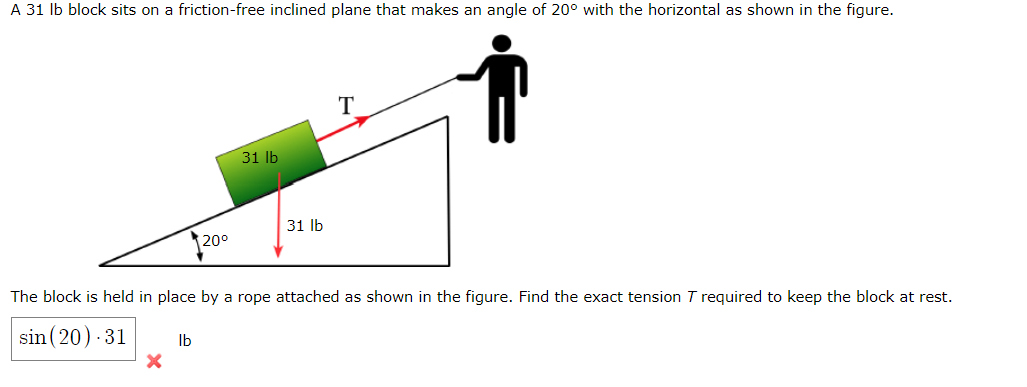

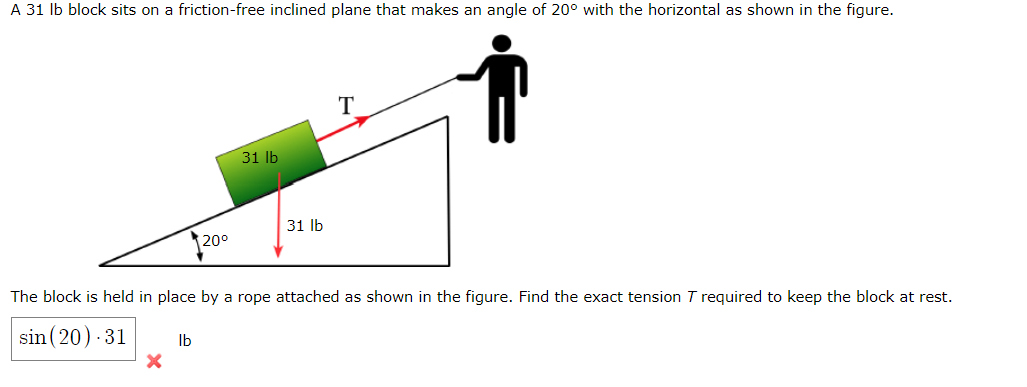

Write Newton’s second law in the horizontal and vertical directions and add the forces acting on the object. Resolve the vectors into horizontal and vertical components and draw them on the free-body diagram. Draw a free-body diagram (which is a sketch showing all of the forces acting on an object) with the coordinate system rotated at the same angle as the inclined plane. Identify known and unknown quantities, and identify the system of interest. To review, the process for solving inclined plane problems is as follows: Be careful not to confuse these letters in your calculations! One important difference is that normal force is a vector, while the newton is simply a unit. For example, the normal force, N N, that the floor exerts on a chair might be N = 100 N. It is important to tell apart these symbols, especially since the units for normal force ( N N ) happen to be newtons (N). This should not be confused with the symbol for the newton, which is also represented by the letter N. Normal force is represented by the variable N. The first step when setting up the problem is to break down the force of weight into components. For inclined plane problems, it is easier breaking down the forces into their components if we rotate the coordinate system, as illustrated in Figure 5.34. Now that you have the skills to work with forces in two dimensions, we can explore what happens to weight and the normal force on a tilted surface such as an inclined plane. Up until now, we dealt only with normal force in one dimension, with gravity and normal force acting perpendicular to the surface in opposing directions (gravity downward, and normal force upward). We discussed previously that when an object rests on a horizontal surface, there is a normal force supporting it equal in magnitude to its weight. The coefficient of friction is unitless and is a number usually between 0 and 1.0, but there is no theoretical upper limit to its value. If the floor were lubricated, both coefficients would be much smaller than they would be without lubrication. Would keep it moving at a constant speed. The harder the surfaces are pushed together (such as if another box is placed on the crate), the more force is needed to move them.į k = μ k N = ( 0.30 ) ( 980 N) = 290 N f k = μ k N = ( 0.30 ) ( 980 N) = 290 N So when you push to get an object moving (in this case, a crate), you must raise the object until it can skip along with just the tips of the surface hitting, break off the points, or do both. Magnifying these surfaces shows that they are rough on the microscopic level. If, on the other hand, you oiled the concrete you would find it easier to get the crate started and keep it going.įigure 5.33 shows how friction occurs at the interface between two objects. If you were to add mass to the crate, (for example, by placing a box on top of it) you would need to push even harder to get it started and also to keep it moving. Once in motion, it is easier to keep it in motion than it was to get it started because the kinetic friction force is less than the static friction force. But if you finally push hard enough, the crate seems to slip suddenly and starts to move. This means that the static friction responds to what you do-it increases to be equal to and in the opposite direction of your push. You may push harder and harder on the crate and not move it at all.

Imagine, for example, trying to slide a heavy crate across a concrete floor. Look at the table of static and kinetic friction and ask students to guess which other systems would have higher or lower coefficients. Explain the concept of coefficient of friction and what the number would imply in practical terms.

Ask students which one they think would be greater for two given surfaces. Start a discussion about the two kinds of friction: static and kinetic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)